Introduction: From Boxing Match to Battlefield Blueprint

Unitree Robotics is not a neutral player in the global robotics race—it is a Chinese company operating under one of the world’s most aggressive military-civil fusion strategies. Founded in Hangzhou, Unitree has already supplied robotic platforms used in military-adjacent environments, including U.S. research labs and Chinese military exercises.

Now, it is preparing to livestream a boxing match between two humanoid G1 robots. Branded as entertainment, the event is actually a public demonstration of adaptive, strike-capable bipedal machines that can be trained for physical conflict.

This report evaluates Unitree’s G1 not as a consumer novelty, but as a field-adaptable kinetic autonomy system developed in a jurisdiction that explicitly incentivizes civilian tech for military repurposing. The fight is real—and so is the strategic threat it quietly introduces.

Confirmed Military Links: Unitree as a Defense-Adjacent Actor

Unitree Robotics is a privately operated, Chinese-based company—officially headquartered in Hangzhou, China, and operating within the PRC’s military-civil fusion (MCF) strategic framework. Under this model, companies are encouraged to design dual-use systems that can be rapidly integrated into defense applications.

Despite claims of neutrality, Unitree’s platforms have already appeared in military contexts across multiple countries:

- In 2024, a Unitree quadruped was showcased carrying a rifle during China-Cambodia “Golden Dragon” joint exercises—a clear example of third-party militarization using Chinese-origin civilian robotics.

- Unitree responded by stating it does not supply weapons, but this line of argument is consistent with MCF: the platform is designed for adaptation, not weaponized by default.

- Meanwhile, U.S. Army Research Labs procured a Unitree GO2 robot for AI research in mobility and control, under a small business federal program.

This establishes Unitree as a global dual-use supplier, not only because of its technology, but because of the political context it operates in: one where commercial robotics are inseparable from strategic defense utility, and export control is deliberately ambiguous.

G1 Combat Capabilities: A Prototype for Human-Sized Force Application

The G1 is Unitree’s first public-facing humanoid robot, and it is being introduced not in a lab, but in a livestreamed fighting match. Beneath the spectacle, the system is a highly adaptable, combat-capable chassis with clear parallels to urban operations robotics, riot suppression, and tactical mobility testing.

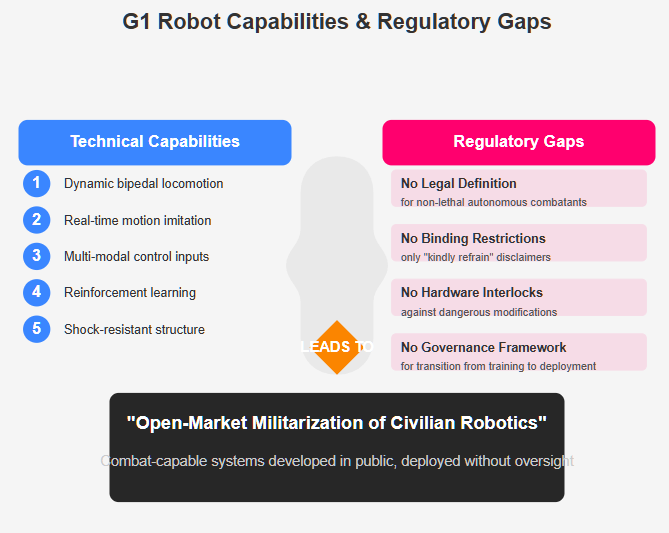

Technical capabilities include:

- Dynamic bipedal locomotion and auto-balancing

- Real-time motion imitation and gesture recognition

- Control via voice, motion capture suit, or direct remote input

- Reinforcement learning that allows G1 to acquire new strike and evasion behaviors over time

- Shock-resistant structure for repeated kinetic engagement

What’s notable is the G1’s military relevance without explicit militarization. The robot is not armed, but it is designed to learn physical engagement autonomously—making it a prototype for non-lethal enforcement bots, urban sentries, or close-quarters AI operators.

Because Unitree operates in a PRC-aligned strategic tech ecosystem, the G1’s development must be viewed not in isolation, but as a testable node in China’s broader strategy to dominate robotics-enhanced warfare. It is not a toy. It is an exportable combat frame—publicly trainable, privately adaptable, and globally unregulated.

The “Kindly Refrain” Clause: Legal Distance, Tactical Reality

Buried in Unitree’s promotional materials for the G1 robot combat event is a line that reveals far more than it intends:

“We kindly request that all users refrain from making any dangerous modifications or using the robot in a hazardous manner.”

This seemingly innocuous disclaimer is, in fact, a legal distancing strategy—one that acknowledges the platform’s potential for dangerous use without placing any enforceable restrictions on it.

In the context of a humanoid robot capable of learning to strike, the phrase “dangerous modifications” carries significant implications. There are no hardware interlocks, no firmware safeguards, and no export-use restrictions preventing users—state or non-state—from transforming G1 units into weaponized kinetic platforms using the weaponization of AI.

Instead of binding terms, Unitree relies on voluntary restraint, effectively pushing the burden of ethical and lawful use onto end users—while still manufacturing and promoting systems designed for physical conflict.

This approach mirrors early stages of algorithmic risk deployment in other sectors: disclaim responsibility, maximize adaptability, and rely on end-user ethics. In the context of humanoid combat robotics, this is a formula for unregulated, plausibly deniable militarization.

No Rules, All Reps: The Legal Black Hole of Humanoid AI Fighters

The G1 exists in a regulatory blind spot. Despite its growing capabilities to engage in physical combat, it is not classified as a weapon, nor is it subject to any binding international restrictions. This is because existing arms control frameworks—especially the Geneva Conventions and the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW)—are built around intent, lethality, and human agency.

None of these frameworks meaningfully address a machine that is:

- Learning to fight through reinforcement algorithms

- Trained on adversarial interactions with other machines or humans

- Designed to be programmable and modifiable for force-oriented tasks

There is no legal definition of a non-lethal autonomous combatant. Nor is there a mechanism to govern or prevent the transition from training simulation to operational deployment—especially when companies disavow liability and provide minimal restrictions.

The G1’s public combat debut highlights this structural gap. It is engaging in real-world physical confrontation under the banner of entertainment—yet it develops capabilities that directly translate into tactical force projection, especially in urban environments, protest control, or asymmetric conflict zones.

Without an updated legal framework, humanoid AI systems like the G1 represent not just a technical milestone—but the erosion of accountability in kinetic autonomy.

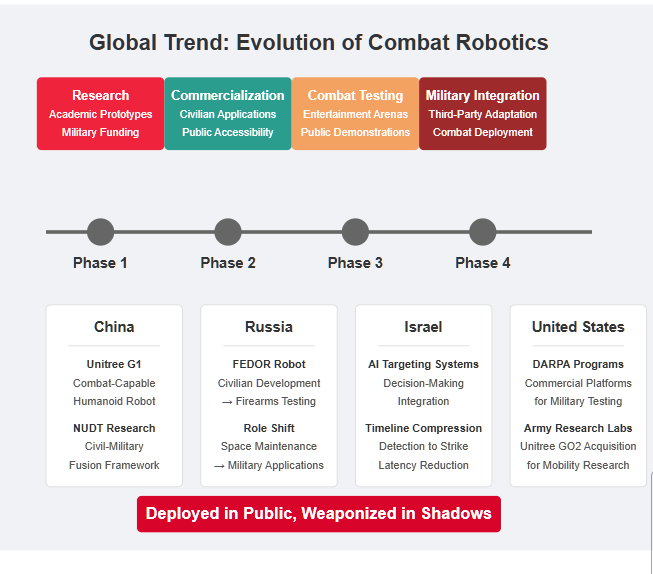

Global Trend: Open-Market Militarization of Civilian Robotics

Unitree’s G1 robot fight is not an isolated development—it’s part of a global trend where publicly accessible robotic systems are being adapted, tested, or deployed in military and paramilitary environments, often with minimal oversight.

Examples include:

- Russia’s FEDOR humanoid robot, initially designed for space maintenance, was later shown firing handguns before being rebranded—demonstrating the fluid boundary between civilian and combat roles.

- China’s National University of Defense Technology (NUDT) routinely blurs academia and military objectives, with dual-use robot systems being developed under the guise of “research.”

- Israel’s semi-automated targeting kill chain integrates AI into live combat decision-making, compressing time between detection and strike.

- U.S. DARPA projects increasingly rely on commercial platforms for prototyping AI-human teaming in dynamic, adversarial environments.

Unitree’s humanoid boxing match fits this pattern: public deployment of combat-capable machines with modular software, modifiable hardware, and no built-in limitations against militarization.

The G1 is a product of the civil-military fusion era, where technological lines are blurred, and systems designed for the market quickly migrate to mission use cases. This should not be viewed as entertainment—it is a real-time proof of concept for kinetic robotics in the open.

Conclusion: Soft Warnings, Hard Capabilities—Time to Regulate

The livestreamed G1 robot boxing match may appear to be a spectacle—but beneath the surface, it represents a significant step in the mainstreaming of combat-capable AI systems. Unitree’s humanoid robot is not theoretical. It is trained to fight, adaptable by design, and already built on a platform lineage with active military exposure.

The company’s vague warnings against “dangerous modifications” highlight a core dilemma: no rules, no restrictions, no accountability. The G1’s capabilities are growing in public—and in the absence of regulation, so is the risk of open-market kinetic autonomy being normalized and deployed.

If policymakers and international bodies fail to act, this isn’t just the future of robot sports. It’s the testbed for the next generation of autonomous force projection—developed in plain sight, and deployed in the shadows.

Humanoid combat AI has entered the ring—and this time, it’s built in China, trained in public, and headed for deployment with no rules in place.