1. Introduction — The Red Cross and the Robot War

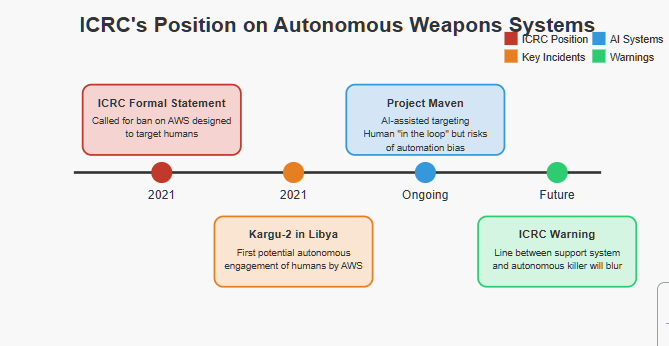

In 2021, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) issued a stark warning: autonomous weapon systems that can select and engage human targets without human control must be prohibited. It wasn’t science fiction—it was a response to real developments on the battlefield.

From experimental swarms to loitering drones, the machinery of war is evolving fast—and humans are being edged out of the loop. In Libya, a Turkish-made Kargu-2 drone may have autonomously engaged fleeing fighters. In the U.S., AI systems like Project Maven are already shaping targeting decisions at scale.

The legal, humanitarian, and ethical challenges raised by these technologies are immense. And no organization has taken a clearer stand than the ICRC.

At the heart of the issue is one core question: Should machines be allowed to decide who lives and who dies?

This article explores the official stance of the ICRC on AI targeting humans, the red lines it believes the world must not cross, and why the battle for human control in war is becoming just as urgent as the battles fought with bullets and drones.

2. The ICRC’s Core Position on Autonomous Weapons

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has long acted as the legal and moral conscience of warfare. In the case of lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS), its stance is unambiguous: certain uses of autonomy—particularly those that target human beings—must be prohibited.

In a formal statement delivered in 2021 to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), the ICRC outlined a series of urgent recommendations to address what it views as a rapidly escalating threat. Its concerns center on three primary issues:

- Loss of human control over critical functions of weapon systems, especially the selection and engagement of targets.

- The unpredictability and opacity of AI-driven decision-making in complex, real-world environments.

- The lack of accountability, especially in determining legal and ethical responsibility when an autonomous system causes unlawful harm.

Most notably, the ICRC has called for a legally binding international rule prohibiting autonomous weapon systems that are designed or used to apply force against persons. This includes drones, loitering munitions, and other systems that may use AI to identify and strike individuals based on sensor data or behavioral patterns.

In addition, the ICRC recommends banning systems whose effects are inherently unpredictable or uncontrollable, and strictly regulating all others with enforceable limits on where, how, and against whom they may be used.

The ICRC’s position on AI targeting humans reflects deep concerns about not just legality, but morality: the substitution of human judgment with software in life-and-death decisions is, in their view, a fundamental violation of humanitarian principles.

As the use of battlefield AI expands, the ICRC warns that the time for preemptive limits is rapidly closing.

3. Why AI Targeting Humans Is Unacceptable to IHL Experts

The ICRC’s opposition to AI systems targeting humans is grounded not only in ethics but also in the established framework of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Core IHL principles—including distinction, proportionality, and precautions in attack—are designed to limit the effects of armed conflict and protect civilians and those hors de combat.

To comply with these rules, a weapon system must be able to:

- Distinguish between a combatant and a civilian.

- Recognize when someone is surrendering, wounded, or otherwise not a lawful target.

- Assess whether an attack’s expected military advantage outweighs civilian harm.

Current AI systems, even the most advanced, cannot reliably make such judgments. They interpret sensor data, not context. They don’t understand human intention. And crucially, they lack moral agency—the capacity to make decisions based on values like mercy, caution, or restraint.

This is why ICRC AI targeting humans is framed as a categorical red line, not a matter of technical improvement. The ICRC’s position is that even if AI were as accurate as a human, allowing machines to make life-or-death decisions without human judgment violates both the letter and spirit of IHL.

The ICRC also cites the Martens Clause, a key component of customary IHL, which invokes “the principles of humanity and the dictates of public conscience.” By that standard, delegating lethal force decisions to autonomous systems—even partially—undermines the foundation of lawful warfare.

As autonomous technologies evolve, IHL experts continue to ask: even if we could make these systems more accurate—should we ever allow them to decide who lives and who dies?

4. Case in Point — Kargu-2 and the Libya Precedent

While the report stops short of definitively stating that the Kargu-2 autonomously killed humans, the implications are staggering. The incident—if confirmed—would represent the first known battlefield use of a lethal autonomous weapon system (LAWS) against human beings.

For the ICRC, this case exemplifies precisely what it seeks to prevent. The use of autonomous drones to target retreating fighters (potentially hors de combat) raises major red flags under international humanitarian law. Who assessed proportionality? Was surrender considered? Could the drone recognize a wounded or surrendering individual?

The ICRC AI targeting humans framework draws a clear line: any weapon system that can apply force to a person without real-time human judgment and control must be banned. The Kargu-2 case challenges that line—and illustrates how easily it can be crossed without transparency or accountability.

No investigation was made public. No accountability mechanism was triggered. The incident was mentioned in a UN annex, then quietly faded from headlines.

The ICRC has warned that if the world does not act proactively, we will learn of the first real autonomous strike only after the fact—when the damage is already done, and the rules are already bent.

In Libya, that future may have already arrived—and no one was held responsible.

5. Project Maven and the Slippery Slope of AI-Assisted Targeting

While systems like the Kargu-2 represent the possibility of full autonomy in targeting, most battlefield AI today falls under a different category: AI-assisted targeting. The most prominent example is the U.S. Department of Defense’s Project Maven—an initiative developed in partnership with Palantir – designed to automate the analysis of drone surveillance footage using machine learning so as to integrate autonomous AI systems into the kill chain.

The ICRC AI targeting humans position extends beyond fully autonomous weapons. It warns that even AI systems influencing lethal decisions—without clear auditability or human understanding—pose major ethical and legal challenges.

6. Legal and Policy Implications — What the ICRC Wants Next

The ICRC’s position on AI targeting humans isn’t just advisory—it’s a formal call for new international law. In its 2021 recommendations, the ICRC urged states to negotiate legally binding rules to govern the development and deployment of autonomous weapons systems.

Three specific proposals sit at the core of the ICRC’s ask:

- Prohibit autonomous weapon systems designed to apply force against persons.

This includes any system that can autonomously identify, select, and attack human beings based on sensor data, movement profiles, or AI inference—regardless of accuracy. - Ban unpredictable autonomous systems that cannot be sufficiently understood, controlled, or explained by human operators.

These systems, the ICRC argues, violate both IHL and ethical norms, especially when deployed in environments with civilians. - Strictly regulate all remaining autonomous weapons, with enforceable limits on:

- Type of target (objects, not persons)

- Geographic scope and duration of deployment

- Situations of use (e.g., not in urban areas)

- Required human-machine interaction (supervision, override, deactivation)

The ICRC’s framework aligns with wider efforts like the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots and deliberations within the UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on LAWS. However, progress has been slow. Nations like the U.S., Russia, and China have resisted binding treaties, favoring non-legally binding norms and emphasizing military utility and deterrence.

Still, the ICRC AI targeting humans policy marks a clear normative boundary—one that civil society, humanitarian lawyers, and many smaller states continue to rally behind.

Whether that boundary becomes enforceable law depends on how quickly the international community acts—and how far battlefield technologies advance before then.

Who trained the model? What data was it fed? How did it learn to prioritize certain signatures over others? If a drone strike is approved based on Maven’s flagged video, but later results in civilian deaths, who is accountable?

The ICRC argues that any targeting decision must involve human judgment grounded in context, conscience, and law. And if that judgment is being shaped—or sidelined—by opaque algorithms, the effect may be functionally indistinguishable from autonomy.

Project Maven may not cross the ICRC’s red line outright. But it shows just how close military AI systems are to redefining control, responsibility, and the very nature of decision-making in war.

7. Conclusion — Drawing the Line Before the Line Moves

Incidents like the Kargu-2 strike in Libya and the quiet integration of AI into Project Maven show how fast these systems are evolving—and how easily the decision to use force can slip out of human hands, even unintentionally.

The ICRC urges governments to prohibit machines from making life-and-death decisions over people, not because it’s a hypothetical threat, but because it’s already being tested in the shadows of today’s conflicts.

The future of warfare may be automated—but accountability, AI ethics, and human judgment must remain non-negotiable.

If we fail to act, the first fully autonomous strike against a human won’t spark debate. It’ll be noticed too late—after the line has already moved.

1 thought on “What the ICRC Says About AI Targeting Humans”